Release time:2025-05-13 16:27:29Clicks:author:SPG ArcheryMain categories:Bows, Arrows, Archery Accessories

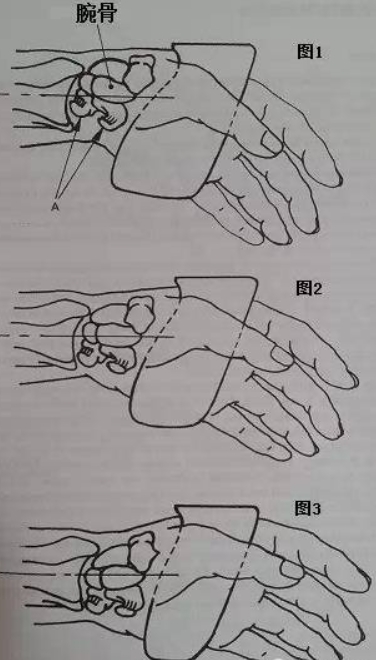

Wrist support The following figure shows three different conditions of wrist bone support.

Schematic diagram of wrist bone support

Figure 1 shows excessive "high push" (the bow push point is at the base of the thumb). The wrist is extended to the extreme and the bow is easily pressed down, causing the arrow to go low; and the wrist bone is rotated and raised, causing the bow push force line to deviate from the center of the wrist bone, requiring greater muscle strength to control the position of the wrist. As the muscles fatigue, the stability and consistency of the movement are difficult to guarantee.

Figure 2 shows a better "high push" (the bow push point is above the thenar eminence). The wrist is properly relaxed, but the bow push force line still deviates from the center of the wrist bone, requiring greater muscle strength to control the position of the wrist.

Figure 3 shows a good bow push wrist posture (the bow push point is in the middle of the thenar eminence, that is, "low push"), the bow push force line passes through the center of the wrist bone, the muscle force required to fix the wrist joint position is minimal, and the stability and consistency are high.

Forearm support beginners are often told to "turn the elbow" in the forearm to avoid the bowstring hitting the forearm. The following figure shows two different conditions of the forearm when it is "not rotating the elbow" and "rotating the elbow".

Schematic diagram of the forearm bone state when "elbow rotating"

In Figure 1, the forearm rotates the elbow clockwise, the elbow socket faces right, and the forearm avoids the path of the bowstring rebound. In Figure 2, the forearm does not rotate the elbow, the elbow socket faces upward, and the forearm is on the path of the bowstring rebound, which is easy to hit the arm.

After the forearm rotates the elbow clockwise, the front hand will naturally tilt to the right, which is one of the reasons for the "oblique holding" technique. Of course, some archers directly adopt the "oblique bow" method, the purpose is to let the front hand be in a natural and relaxed state, and use as few muscles as possible.

Schematic diagram of the natural state of the hand after "elbow rotating"

The figure below shows the shoulder bones and joint structure of the human body.

Schematic diagram of the shoulder bone structure

The "upper arm bone" is directly connected to the "scapula", and the "clavicle" is connected to the "sternum" and "scapula". The bow force borne by the "upper arm bone" is transmitted to the body through the "clavicle" and "scapula" to be supported.

It should be noted that the connecting joint between the "upper arm bone" and the "scapula" and the connecting joint between the "clavicle" and the "scapula" are not on the same straight line. If we use a simplified diagram to represent it, we can draw such a "connecting rod structure" diagram.

Schematic diagram of simplified connecting rod structure of the shoulder

Under such a bone structure, if the forearm is raised higher (as shown in Figure 1 below), the forearm support force line is higher than point A (the connecting joint between the "upper arm bone" and the "scapula"), and just passes through point B (the connecting joint between the "clavicle" and the "scapula"), then the muscle force required for support is the smallest, and it is also the easiest to achieve stability.

Schematic diagram of forearm support force line and joint position change

As shown in Figure 2, if the forearm support force line is lower than point B (the connection joint between "clavicle" and "scapula"), but just passes through point A (the connection joint between "upper arm bone" and "scapula"), it can also obtain good bone support, but some subtle changes (such as lowering the forearm height when shooting low targets, or changes in the ratio of the bow's own weight and the draw weight) will cause "shrugging".

If the forearm position is low (as shown in Figure 3), when the forearm support force line is completely lower than point A (the connection joint between "upper arm bone" and "scapula"), the shooter's insufficient shoulder muscle strength is likely to cause "shrugging". This is why many beginners are prone to "shrugging" when shooting at a standard target position of 1.3 meters high at close range.

Diagram of the reason for "shrugging" in close-range shooting

The improvement method is to keep the "cross" line between the two shoulders and the spine unchanged, and lean the body slightly forward toward the target, so that the position of the shoulder joint is lower than the support force line of the forearm, and use the bow force to "press down" the front shoulder to form a good "bone support".

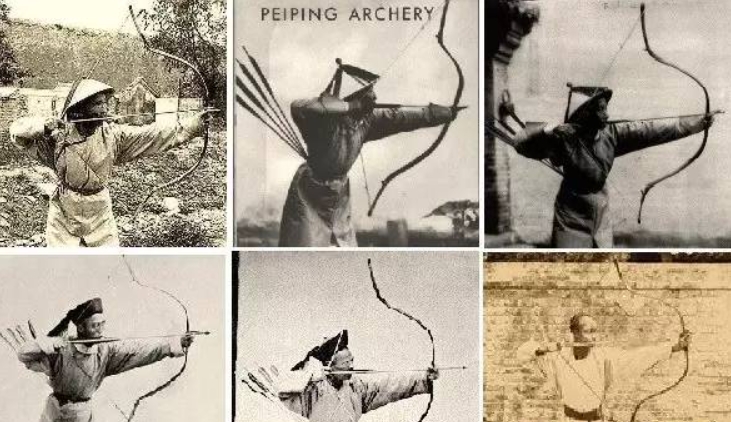

Miscellaneous After understanding these human body structure knowledge, looking back at the traditional archery posture, we will have some interesting discoveries: many archery pictures and old photos show the front hand raised high, higher than the shoulder, and even some basic "frame" training in Qing Dynasty archery books also requires this posture.

Qing Dynasty archery frame, forearm raised high

Is this just because ancient archery was all about shooting at distant targets, or is there a meaning of getting better "bone support" in it? If this is the basic "frame", then how do they shoot close-range targets?

There is an interesting picture in Ray Axford's book, showing that in order to get better "bone support" for the front shoulder, ancient Western archers often adopted the method of "leaning the body forward toward the target"

The forward-leaning shooting posture in ancient Western archery paintings

Even in ancient paintings handed down from China, there are many examples of this shooting posture.

The forward-leaning shooting posture in ancient Chinese archery paintings

I didn’t feel deeply about this when I used bows below 40 pounds before. Later, when I started using 50- and 60-pound bows, I often felt that it was difficult to support the front shoulder, and the shoulder muscles would ache after long-term shooting. After changing to this method, the support of the front shoulder is much more stable, and the muscles are no longer painful. No one studied anatomy in ancient times, but what our ancestors summed up in practice is indeed wise...

Writing this, I must be careful to say: These physiologically reasonable action essentials are not necessarily the most suitable technical actions for accurate shooting. The bows used in accurate shooting competitions generally do not have great bow power. Well-trained archers can control the positioning of the shoulders with muscle strength, and keeping the body upright is easier to maintain consistency than "leaning the hips forward". At least in my personal experience, "leaning the hips forward" requires a lot of training to ensure consistency of action. Perhaps, a more appropriate statement is: This is the reasonable way of "martial shooting" heavy bows summed up by our ancestors in practice