Release time:2025-08-27 15:35:50Clicks:author:SPG ArcheryMain categories:Bows, Arrows, Archery Accessories

According to Chinese legend, the Yellow Emperor ordered his subordinates to make bows and arrows. However, the earliest stone arrowhead discovered in China dates back to 28,130 ± 1,330 years ago, found in Zhiyu Village, Shuo County, Shanxi Province, predating the agricultural civilization of the Yellow Emperor. Clearly, humans first learned hunting and then developed agriculture. This arrowhead is one of the earliest, if not the earliest, in the world (archaeologists generally agree that the bow and arrow were invented in Africa 20,000 to 30,000 years ago, and in Europe 18,000 years ago). Based on archaeological artifacts, the Yellow River Basin in China may be the first region in the world to invent the bow and arrow. Ancient Chinese mythology also contains the legend of "Yi Shooting Nine Suns." The protagonist of this story, Yi, was banished to the mortal world and became the leader of the Dongyi tribe. Historically, the Dongyi tribe was also known as Houyi, a powerful leader. The line between legend and history becomes blurred in this individual. The Dongyi people ranged from present-day Shandong and northern Jiangsu, and had frequent contact with the agricultural peoples of the Central Plains. Ancient history records that a Xia king, "Zhao," invented armor specifically to counter the arrows of Eastern peoples. While ancient historical records do not represent actual facts, the Dongyi, a fishing and hunting tribe, were skilled in archery, a fact that seems to have left a deep impression on the Central Plains tribes of the time.

Speaking of the Dongyi, it is also worthwhile to explain China's northern ethnic groups. The Dongyi and what later became known as the Northern Di shared geographical connections and also engaged in cultural exchange. The Dongyi were early adopters of the Central Plains agricultural culture, while the nomadic Northern Di developed into the numerous northern ethnic minorities that later characterized Chinese history. By the late Eastern Zhou Dynasty and the Warring States Period, the various northern ethnic groups had merged and unified into the Xiongnu and Donghu tribes. With the addition of the Sushen people of Liaoning and Jilin, all the northern ethnic groups that had troubled successive Central Plains dynasties had emerged. The Xiongnu flourished in the northern desert for 500 years, threatening the Qin and Han dynasties. After the Xiongnu's decline, the Turkic peoples who followed them were their direct cultural and kinship successors. The Khitan Liao Dynasty and the powerful Mongol Yuan Dynasty, both of which belonged to the Donghu clan, also belonged to the Jurchen Jin and Qing dynasties, direct descendants of the Sushen, and each established its own dynasty in Chinese history. Almost all Han Chinese historical texts describe these peoples as "excellent at riding and shooting" or "skilled in horsemanship." The northern peoples, represented by these peoples, battled for supremacy with the might of cavalry and the skill of bows and arrows, exhausting successive Central Plains dynasties and adding a powerful vein to the Chinese nation.

Over two thousand years of feudal history, the halberd and halberd disappeared as weapons, the sword also declined, and the spear and sword constantly adapted to the development of warfare. However, China's traditional bow and crossbow have remained enduringly popular. The crossbow is a close relative of the bow. While the two are used interchangeably in my country, this isn't necessarily the case in other countries. While bows were common in many nations and cultures during the cold weapon era, crossbows were uniquely developed, with China being almost the only country in the world to have developed this weapon to its full potential. When did the crossbow originate in China? Qiao Zhou of the Three Kingdoms period claimed that "Huangdi invented the crossbow," a clear allusion to history. The "Wu Yue Chunqiu" states that "the crossbow originated from the bow, and the bow was born from the slingshot," clarifying the relationship between the crossbow, bow, and slingshot (a more scientific explanation). A crossbow is a bow held horizontally with the arm, and the rear of the arm is equipped with a mechanism for stringing, firing, and aiming—the crossbow trigger. Recent records indicate that the earliest crossbow fragments in China were unearthed in Qingzhou, Shandong Province. That stone crossbow has been dated to over 3,000 years ago. Chinese crossbows were widely deployed during the Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period. By the Qin and Han Dynasties, they had become the most numerous weapon in the imperial army. Large crossbows appeared in the late Eastern Han Dynasty, further developed during the Tang Dynasty, and reached their peak of glory during the Song Dynasty before gradually declining.

The crossbow, derived from the bow, was more powerful and easier to aim. The Chinese crossbow has a history of at least 3,000 years (image added by the blogger). Modern historians studying ancient Chinese crossbows must refer to two key points: the Zhou Dynasty's "Kaogongji" (Records of the Craftsmen) and Confucius's "Six Arts." The "Kaogongji" sections, "Bowmen" and "Arrowmen," detail the manufacturing techniques of bows and arrows at the time. For over 2,000 years, these techniques have been revered by archers as "Gao Gui." The Chengdu "Changxing" bow shop in the 1940s and the "Juyuanhao" bow shop, the only remaining in China, both manufacture bows and arrows according to traditional techniques. Despite some differences in name, their specific manufacturing processes adhere to the principles of the "Kaogongji."

Confucius, the founder of Confucianism, had a profound influence on Chinese culture. He proposed the "Six Arts" as mandatory skills for a gentleman, one of which was archery. Confucius restored the Zhou rituals, and during the Zhou dynasty, archery was highly respected, with archery even becoming a criterion for determining one's virtuousness. Beyond its military significance, archery was also a form of etiquette and a symbol of social status, with detailed regulations for archery rituals found in the Book of Rites. Of course, not all Chinese scholars practiced archery for show. During the martial-minded Tang Dynasty, a Jinshi (Jinshi) named Xue Gongda served as a staff officer in the Fengxiang army. During a military archery competition, the target was over a hundred feet away, and none of the soldiers were able to hit it. However, this scholar "shot three times in a row, hitting the target, and if it was broken, it could not be shot again," completely destroying the target. After his death, Han Yu included this event in his epitaph, citing it as a lifelong achievement. Archery was one of the six arts in ancient China, and skill even determined a scholar's social status.

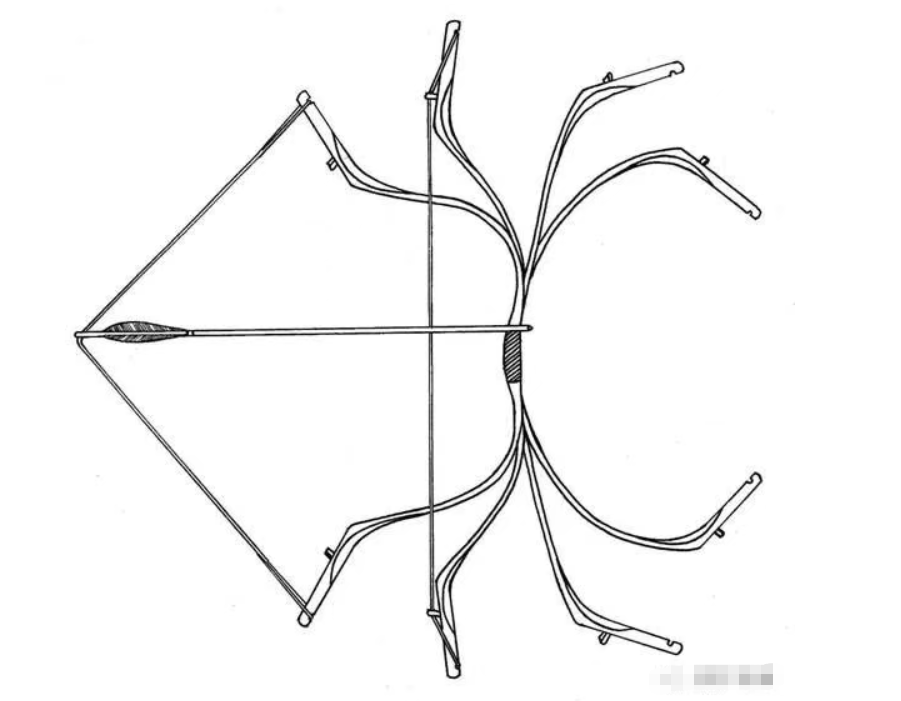

When we talk about traditional Chinese bows like Mongolian or Qing Dynasty bows, they are generally described as "hyperbolic recurved compound bows," which leads to a classification of bows.

Bows are categorized by the material used to make them: monolithic bows and composite bows. Monolithic bows are made of a single material, and the earliest bows were monolithic. Composite bows are constructed from a variety of materials, with mature composite bows mostly made from bamboo, wood, animal tendons, and horn and bone. Chinese bows entered the era of composite bows around the Shang Dynasty. Monolithic bows didn't evolve directly into mature composite bows during technological development. Initially, several bamboo and wood materials with different mechanical properties were bonded together to improve the bow's performance. British scholar Pitt-Rivers called these bows reinforced bows or, more vividly, laminated bows. The traditional Japanese bow is a typical reinforced bow, constructed from two, three, four, or five reinforced pieces of wood. Even the most common bows used in Japanese kyudo halls today are made from eight or nine reinforced pieces of wood.

Traditional Japanese Bows and Horseback Archery

The most famous European bow for individual soldiers is undoubtedly the English longbow, a standard single-piece bow with a bow body made from hardwoods such as yew and elm. The English longbow enjoyed its golden age of military success from the 13th to 16th centuries, until it was eventually replaced by the matchlock. The traditional Chinese bow is a composite bow, a descendant of the Mongolian bow more familiar to Westerners, as described in the Kaogongji (Kaogongji). This type of bow is made from a wood or bamboo frame, with angled pieces attached to the inside to withstand the pressure of bending and animal tendons attached to the outside to withstand tension. The different materials are bonded together with animal glue, greatly improving the mechanical properties of the frame, making it one of the earliest "composite materials." Because the bows are affixed with animal horn pieces, they are also generally referred to as "horn bows." These bows are often mentioned in classical literature. Later scholars, lacking a thorough understanding of bows, interpreted them as bows decorated with horn, which is incorrect. By using animal horn and tendons to improve their load-bearing capacity, compound bows can deliver more energy to arrows with a shorter length, making drawing easier. Their smaller size also makes them easier to shoot from horseback.

A cross-section of a traditional compound bow shows the light-colored bamboo core in the middle as the bow frame, the darker layers below as the horn pieces, and the tendons above the bamboo core. The tendons and horn are glued to the bow frame with animal glue, then wrapped with silk thread and coated with glue and lacquer. Sometimes, the bow is also covered with bark or animal skin to protect it from moisture. (The above three images are from the Asian Traditional Archery Research Network, www.atarn.org) A "recurve bow" refers to a bow that is relaxed when unstrung. Its curvature is opposite to that when strung, with some or all of the bow bow curving forward. This indicates the bow's greater elasticity. Most compound bows are recurve bows, and due to the incorporation of animal tendons, they are capable of a greater degree of curvature. Generally speaking, a flexible bow is first bent and tightened to a certain degree before being used for shooting, which helps maximize the efficiency of the bow material. Since there are "recurve bows," there are also bows that do not bend forward when unstrung. These are generally single-body bows. A typical compound recurve bow exhibits two graceful arcs when strung, creating an "M" or "W" shape. This is why it's also called a "double-bend," as opposed to the more common "single-bend" bow.

Recurve and hyperbola are typical characteristics of Asian composite bows. [Related Link] Experiments have been conducted comparing Turkish bows with European longbows. The Turkish bow, derived from the bows used by the Turks and similar to the Mongolian bow, is a typical composite bow. The experiments showed that, at similar full-draw draw weights, the composite bow is smaller than the monolithic bow, yet produces a higher initial velocity and kinetic energy. From a physics perspective, the process of drawing an arrow is essentially the archer storing energy in the bow, which then transfers this stored mechanical energy to the arrow. To increase the mechanical energy stored at full draw, the length, width, and thickness of the limbs' elastic parts must be increased. The thickness of the limbs has the most significant impact on bow force. Consider some modern Chinese war bows, which have very thick limbs and heavy bodies. Monolithic European bows, however, were limited by the availability of wood, and generally increased their length to improve performance. Later, crossbows with steel limbs emerged in Europe, directly replacing the limited mechanical properties of wooden limbs. The most basic metric for describing a bow's performance is its draw weight. The force exerted on the bowstring when the bow is fully drawn is the bow's overall draw weight. Bows used in international sports competitions today typically have a draw weight of around 40 pounds. For example, in the Olympics, women use bows weighing 20 to 40 pounds, while men use bows weighing 30 to 50 pounds. While 50 pounds weighs approximately 23 kilograms, it might not seem like a lot. However, for an untrained archer, drawing a 50-pound bow is far more demanding than lifting a 23-kilogram object. However, professional archers with extensive training can sometimes achieve astonishing levels of draw weight. Historical records show that a few ancient warriors could even draw war bows weighing around 400 pounds. These skilled archers are described as having broad chests and backs, often referred to as "ape arms." This is for a reason: bow drawing primarily utilizes the chest and back muscles, and ape arms refer to long, slender, and flexible arms. The British philosopher Francis Bacon said that practicing archery can broaden one's mind, and this holds true from a physiological perspective. Regular and extensive chest expansion exercises, combined with calming the mind and limiting distractions when aiming, are indeed beneficial to both physical and mental health.

Generally speaking, the drawstring force of a basic single-strand bow increases linearly with draw distance. However, with traditional Asian compound bows, archers will experience uneven draw force. Bow makers claim that the most demanding part of the draw occurs about halfway through, while the full draw is slightly easier. Modern scientific experiments have partially confirmed this claim. (To be continued)